Colonising Africa: What happened at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885?

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 was a defining moment in the colonisation of Africa, marking the formal division of the continent among European powers without the involvement or consent of African nations. The late 19th century was a period of rapid industrialisation across Europe, and African resources became increasingly attractive to fuel this growth. European countries sought direct control over these resources, moving beyond trade relationships to territorial ownership. This ambition led to the infamous “Scramble for Africa,” where powerful European nations rushed to claim vast areas of the continent.

European nations like Great Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, and Belgium began sending representatives to African regions to negotiate trade and sovereignty agreements with local leaders. In many cases, they simply raised their flags to signify ownership. The competition for territory soon led to disputes between these powers. For instance, there were tensions between Britain and France over territories in West Africa, as well as between France and King Leopold II of Belgium regarding areas in Central Africa. To prevent these disputes from escalating into armed conflict, European leaders agreed to meet in Berlin to establish clear guidelines for territorial claims and manage the colonisation process in an orderly manner.

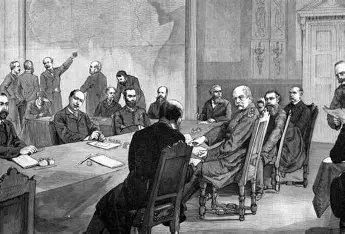

The Berlin Conference, convened by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, began on November 15, 1884, and continued until February 26, 1885. It was held at Bismarck’s official residence in Berlin and brought together representatives from 14 nations. However, no African representatives were invited, meaning that the fate of the continent was decided without the voices or perspectives of those who lived there. A request by the Sultan of Zanzibar to participate was denied, further highlighting the exclusion of African interests.

The primary objectives of the conference included defining territorial claims, establishing rules for future annexations, and ensuring free trade and navigation, particularly in the Congo and Niger River regions. The major powers present were France, Germany, Britain, and Portugal, who held the most African territory at the time. Belgium’s King Leopold II also sent representatives to secure international recognition for his “International Congo Society,” which was a front for his personal ambitions to control the Congo Basin.

The other nations represented at the conference, including Austria-Hungary, Denmark, Russia, Italy, Sweden-Norway, Spain, the Netherlands, the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), and the United States, played minor roles. Many of these countries did not receive any African territory as a result of the conference, with the most significant gains going to the major colonial powers.

The outcome of the Berlin Conference was the signing of the General Act, which consisted of 38 clauses that formalised the division of Africa. This act allowed European powers to claim African territories by demonstrating “effective occupation,” meaning they had to establish administrative control rather than just planting a flag. This provision accelerated the colonisation process. While only 20 percent of Africa was under European control before the conference, by 1890, five years later, nearly 90 percent of the continent was colonised.

One of the most significant results of the conference was the recognition of King Leopold II’s control over the Congo Free State. Although Leopold portrayed his activities as humanitarian, his administration was marked by extreme violence and exploitation. The local population suffered under forced labour, particularly on rubber plantations, and brutal punishments such as amputations were common. This period is now remembered as one of the most horrific chapters of colonial exploitation in Africa.

The Berlin Conference also reinforced the suppression of the slave trade, which had been officially abolished in the early 19th century but continued illegally in some regions. Despite these provisions, the primary goal of the conference was to serve European economic and political interests rather than protect African populations.

The division of African territory was not fully finalised at the Berlin Conference but continued through bilateral negotiations and further agreements following World War I. During this period, the German and Ottoman Empires collapsed, allowing other European powers to expand their holdings. The final colonial map of Africa by the early 20th century saw France controlling vast areas of West and Central Africa, Britain dominating southern and eastern regions, and Portugal, Germany, Belgium, Italy, and Spain claiming smaller territories. Only two African nations—Liberia, founded by freed African Americans, and Ethiopia, which resisted Italian colonisation—remained independent.

Although the Berlin Conference did not initiate the colonisation of Africa, it accelerated the process and gave it a legal framework. African societies, which had long-standing cultural, political, and economic systems, were forcibly integrated into European empires. The arbitrary borders drawn by European powers ignored existing ethnic, cultural, and linguistic divisions, which led to internal conflicts that persist to this day. African communities were often grouped together despite historical rivalries, while others were separated from their traditional lands.

The long-term consequences of colonisation have been profound. The exploitation of Africa’s natural resources enriched European nations while leaving African societies economically underdeveloped. After World War II, African nations began to fight for and achieve independence, but the colonial legacy left deep scars. The political fragmentation caused by artificial borders created challenges for nation-building, and many newly independent African countries faced civil wars and political instability.

Military governments took power in several countries, such as Nigeria and Ghana, and these regimes often hindered democratic development. Today, the effects of colonisation continue to shape African geopolitics. In some regions, there is ongoing resentment toward former colonial powers, as seen in countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, where military governments have accused France of neocolonialism.

Julius Nyerere, the former president of Tanzania, captured the enduring impact of the Berlin Conference when he remarked that Africa was left to struggle with artificial nations created by European powers. The legacy of the Berlin Conference remains evident in the political, social, and economic challenges faced by African countries today. The arbitrary divisions and the exploitation that began in 1884-1885 continue to affect the continent, highlighting how deeply colonialism has shaped modern Africa.